Anasazi Pottery

Evolution of a Technology

Pottery is ubiquitous on Anasazi archaeological sites (Figs. 1 and 2), and it is both one of the aesthetic joys and most powerful tools of the archaeologist. The beauty of Anasazi pottery was one of the primary motivations behind the early archaeological expeditions to the Southwest; the shelves of museums are stocked with exquisite display specimens. But as this motivation was satisfied, and as knowledge about the inner workings of ancient cultures became more important, pottery was seen in a different light. Consistent progressions of decorative style were defined across the region with the help of stratigraphy and tree-ring dating, and those styles in turn became the basis for one of the most precise ceramic chronologies in the world. Simultaneously, geographic variations in raw materials were documented and became the basis for studies of prehistoric exchange networks. These two aspects of Anasazi pottery are now nearly taken for granted in Southwestern archaeological research, and attention is once more being directed toward pottery itself. However, instead of its beauty, archaeologists are now studying pottery technology: its origins, changes within the craft, and the organization of pottery production within Anasazi society.

Anasazi Pottery

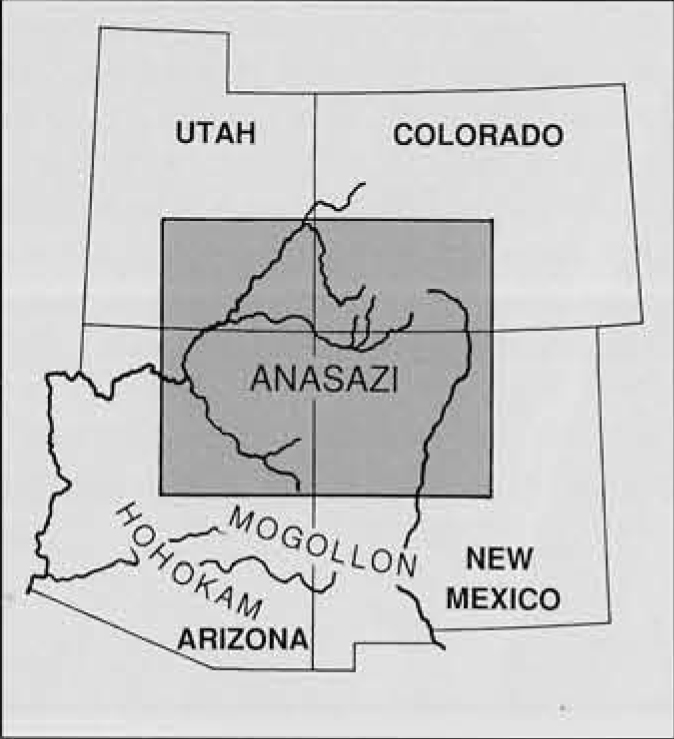

Anasazi pottery is distinguished from that of other Southwestern culture areas by its predominant colors (gray, white, and red), a coil-and-scrape manufacturing technique, and a relatively independent stylistic trajectory. Speculation about its origin has centered around diffusion from Mogollon and ultimately from Mesoamerican cultures to the south, but the stark contrasts between Mogollon brown and Anasazi gray and white pottery have also raised the possibility of independent invention through accidental burning of clay-lined baskets (Morris 1927). However, the contrasts are usually drawn between fully developed examples of both Mogollon and Anasazi pottery traditions (Fig. 4). Recent research by Dean Wilson and colleagues has pointed to underlying similarities of the earliest pottery throughout the upland Southwest (Wilson and Blinman 1991; Skibo et al. 1992).

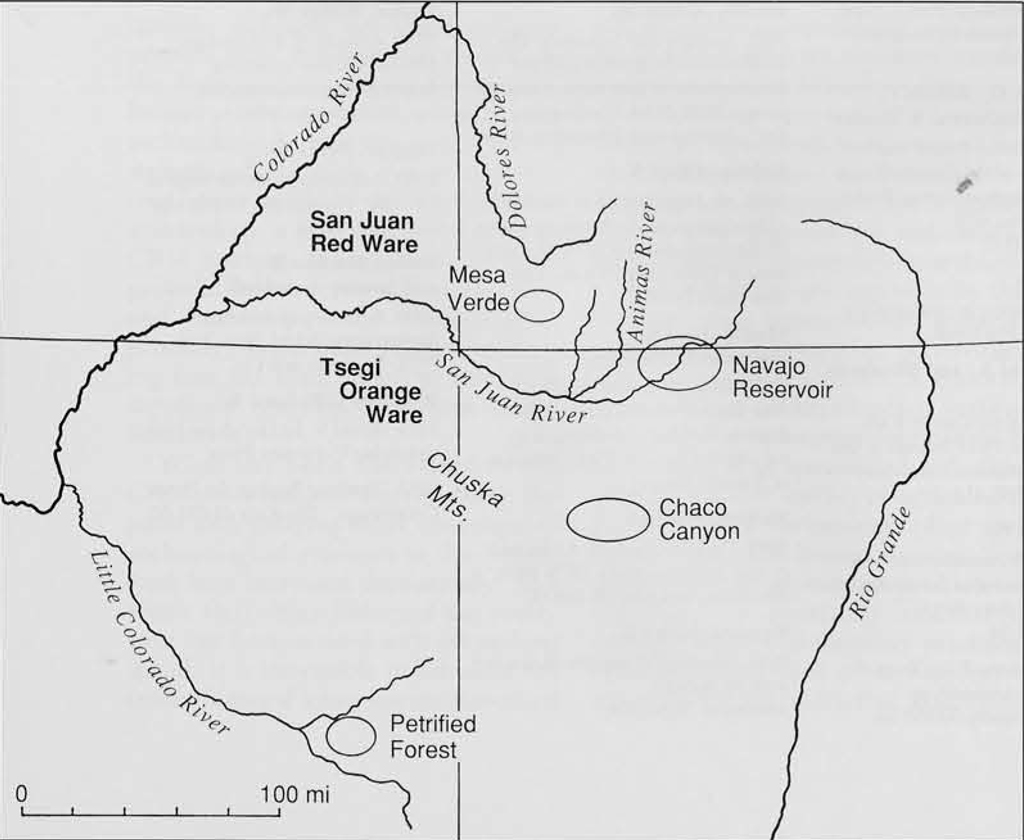

Pottery occurs as early as A.D. 200 in the Anasazi region, and most

of this pottery appears to have been made of floodplain or soil clays.

These alluvial clays are often usable as they come from the ground, and

the high iron content of the clay resulted in a brown surface color.

An open fire on the ground surface would have proved adequate for

firing. The best known of these early pottery sites are in the Petrified

Forest National Park and the Navajo Reservoir area of northern New

Mexico, where a crumbly brown ware is present on sites dating within

the A.D. 200-500 period. By A.D. 500, the durability of the brown ware

improved, and it was joined by a gray ware pottery. By A.D. 600, Anasazi

potters focused their attention on the gray ware technology, and brown

wares were no longer manufactured.

Fig. 2. Mug House, Mesa Verde National Park. Some Anasazi sites,

especially those of the Pueblo III period, remain remarkably well

preserved today in protected rock shelters. These cliff dwellings were

among the first to yield examples of the potters’ art to archaeologists,

and the Mesa Verde pottery style became a modern symbol of the Anasazi

culture.

Fig. 2. Mug House, Mesa Verde National Park. Some Anasazi sites,

especially those of the Pueblo III period, remain remarkably well

preserved today in protected rock shelters. These cliff dwellings were

among the first to yield examples of the potters’ art to archaeologists,

and the Mesa Verde pottery style became a modern symbol of the Anasazi

culture.The transition to Anasazi gray wares appears to have resulted from the adaptation of brown ware production techniques to new raw materials. As the brown ware technology moved northward from the Mogollon area, potters continued to seek out floodplain or soil clays, ignoring for a time the geologic clays that were abundant as shale layers within the sandstone cliffs of the Four Corners landscape. Most of these geologic clays have high shrinkage ratios, and potters would have had to modify the clays before use. Also, unlike the alluvial clays, the geologic clays appear to perform best when fired under neutral rather than the oxidizing conditions of an open fire. Experimentation with the geologic clays began in the 6th century, and by the beginning of the 7th century the technology had been fine-tuned, setting the stage for the next 600 years of Anasazi pottery production.

The Gray Ware Cooking Pot

The foundation of the Anasazi ceramic tradition was the cooking pot.

As maize became a significant part of the Anasazi diet, boiling became

increasingly necessary as a food preparation technique. Although food

can be boiled in baskets, pottery vessels have a number of advantages:

pots are less time-consuming to produce, fuel use is more efficient, and

the same container can serve for dry storage, wet storage, and cooking.

Pots are brittle, however, and better suited to sedentary rather than

mobile lifestyles. The Four Corners environment was perfect for feedback

between agriculture, sedentism, and pottery technology, and pottery

rapidly became an integral component of Southwestern culture (LeBlanc

1982).

Modern ceramic technology can be extremely intricate, producing products as diverse as building brick, porcelain, and space shuttle heat shields. In Anasazi culture, the initial goal was to produce a durable cooking pot. Although outwardly simple, the cooking pot is a delicate compromise between conflicting technological and functional demands. Anasazi geologic clays swell and shrink so much on wetting and drying that vessels of pure clay would crack prior to firing. Non-swelling material (temper) can be added to the clay to reduce and control shrinkage, but temper reduces the strength of the vessel wall. The potter can control the effect of temper on strength by altering the shape, size, and material of the temper particles. Angular tempers form stronger bonds with the surrounding clay, finer tempers distribute weaknesses more evenly, and tempers that have a similar coefficient of thermal expansion to that of the surrounding clay create fewer flaws during the high heat of firing and subsequent cooling.

https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/anasazi-pottery/

%20Anasazi%20-%20search%20results%20Facebook.png)

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten